Recent climatic variations, combined with current cultivation, harvesting, storage, and feeding techniques, have made contamination of silages and cereals and their derivatives by fungi, particularly Aspergillus spp but even more Fusarium spp, increasingly frequent. The latter produce a wide range of mycotoxins, some of which are poorly understood but highly harmful to cattle.

Clinical pictures observed in the field are diverse, though often characterized by symptoms easily recognizable by the farmer, such as infertility, digestive metabolic disorders, increased risks of enterotoxemias, orchitis, agitation, tail necrosis, hemorrhagic diarrhea, and even inflammation of the limbs hoof diseases.

It is possible, or rather necessary, especially in particular years or specific periods of the year, to prevent the problem with interventions both on feeding and with proven effective products. (Informatore Zootecnico, Carlo Angelo Sgoifo Rossi, Riccardo Compiani, Gianluca Baldi – March 10, 2015).

But what are mycotoxins?

Mycotoxins are toxic substances (to other forms of life), with low molecular weight, naturally produced by the secondary metabolism of microscopic filamentous fungi (or molds) that develop under specific environmental conditions, both in the field and during the harvesting and storage of cereals, forages, and other simple or compound feeds.

Some feeds are more susceptible to fungal growth than others. These molecules exhibit great chemical variability and can induce both acute and/or chronic toxicity in animals and humans.

Among the various groups of mycotoxins, the only common characteristic besides being produced by molds is their great resistance to high temperatures, chemical treatments, and subsequent storage and processing of the affected feeds. Mycotoxins do not induce an immune response, and their effects can be neuro-, nephro-, hepato-, dermo-, entero-toxic, as well as immunosuppressive, carcinogenic, and teratogenic.

The list or classification of mycotoxins and their producing molds is quite long and constantly expanding, redefined in light of the ongoing discovery of new mycotoxins or new effects of already known ones. It is, however, useful for practical classification purposes to first distinguish molds based on where they develop, i.e., in the field or in storage sites.

The development of “field molds” is favored by a high degree of humidity (>70%) and significant temperature fluctuations (hot days followed by cold nights).

On the other hand, “storage molds” develop quickly and easily in forages after harvest as well as in storage sites of cereals, oilseeds, and feeds with moisture content exceeding 15% for a period of time.

The presence of oxygen (molds are obligate aerobes, although they can grow in very low oxygen concentrations (4%) – microaerophilic environment), high humidity, and reduced acidification of the silage mass stimulate their development. The absorption of mycotoxins occurs mostly through the digestive system before acting with a specific mechanism for each one.

The ruminal environment in ruminant animals represents a barrier capable of inactivating a significant portion of mycotoxins, making the ruminant resistant to intolerable concentrations for monogastric animals. The detoxification activity in the rumen, in most cases, generates less toxic metabolites of the reference mycotoxin, contrary to some metabolites where toxicity is enhanced (e.g., zearalenone α-zearelenol).

The detoxification capacity of the ruminal protozoan population, which plays a predominant role, varies according to the class of mycotoxins and the contribution of other microorganisms and bacteria, whose activity is often underestimated. Some ruminal bacterial strains can indeed degrade certain mycotoxins.

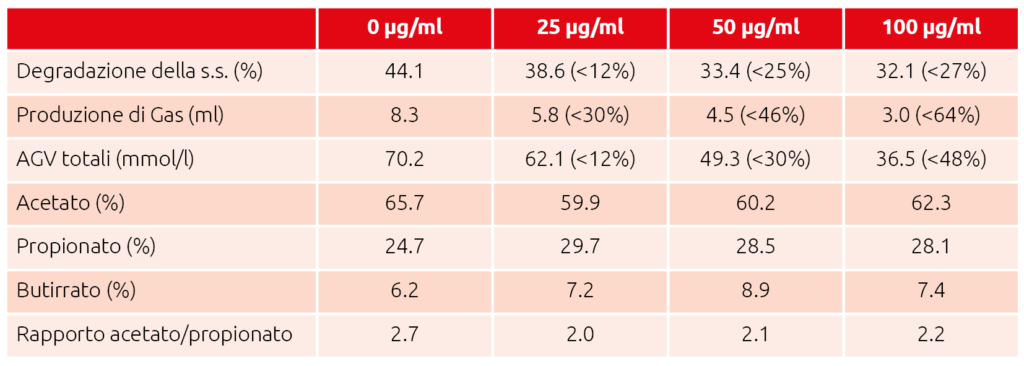

Table 1

Table 1

Effect of different concentrations of Patulin on ruminal fermentations in vitro 10.

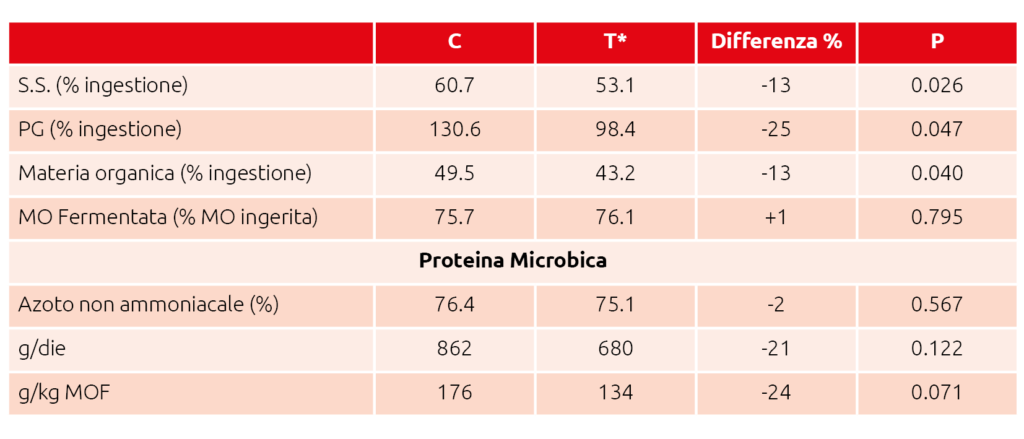

Table 2 – Passage of nutrients to the intestines of cows fed wheat contaminated with Fusarium spp. toxins 11.

*T: diet containing wheat contaminated with DON 7.15 ppm and ZEA 186 ppb.

However, the detoxification capacity of the rumen is saturable and affected by various concurrent aspects such as ruminal pH, diet type, changes in diet, or metabolic diseases.

Many mycotoxins, in turn, have antimicrobial, antiprotozoal, and antifungal effects on the ruminal flora. Indeed, parameters indicative of good ruminal functionality such as the percentage of dry matter degradation, gas production or volatile fatty acids, and the amount of microbial protein produced are significantly compromised in the case of mycotoxicosis, as evidenced by the results of studies reported in Tables 1 and 2 (C.A. Sgoifo Rossi et al. Large Animal Review 2011).

Mycotoxins are likely a factor contributing more to chronic problems than acute ones, such as high incidence of diseases, suboptimal milk production, and/or altered reproductive performance.

The most stressed cows, such as those fresh from calving, are more easily affected, with a wide-ranging and non-specific symptomatology.

We can identify 5 mechanisms of action:

1. Reduction in dry matter intake.

2. In contaminated feeds: alteration of nutrient content, absorption, and metabolism.

3. Alteration of endocrine and exocrine systems.

4. Suppression of the immune system.

5. Altered microbial growth.

The target organs are primarily the liver and kidneys, with general consequences on the entire immune system. The altered immune response associated with peripheral vasoconstriction underlies the related problems that can also manifest at the hoof level. In particular, some toxins have been studied that would be particularly involved in these manifestations.

Ergot Alkaloids (Claviceps Purpurea)

Ergot alkaloids are mycotoxins produced by a fungus of the genus Claviceps, more specifically Claviceps Purpurea, an ascomycete that parasitizes grasses, primarily rye, but also other cereals such as wheat, spelt, and oats. Claviceps Purpurea is the most studied and known species for its significant effects in contaminating foods made from infected cereals.

This species generates, in infected plants, growths (sclerotia) similar to “spurs”, in French “ergot” or often—like in the case of rye—horn-shaped protrusions, the fruiting bodies of the fungus itself, containing various toxic or psychoactive alkaloids from the ergotine group, hence the name Ergot Alkaloids, and also the common name of ergot rye.

The atmospheric conditions that favor the development of Claviceps Purpurea are humid weather, rain, and cold, especially in spring during cereal flowering. After infecting the ovary, the fungus grows along with the kernels of the spike, forming sclerotia, which usually have an elongated shape compared to seeds and are dark-brown in color. (https://veterinariaalimenti.sanita.marche.it/Articoli/category/igienedegli-alimenti/micotossine-emergenti-gli-alcaloidi-dellergot)

Ergot alkaloids can induce severe vasoconstriction of small arteries. The body areas most affected are the extremities, ears, and tail. This can lead to lameness in ruminants and, in extreme cases, inflammation of distal joints can result in hoof loss or gangrene.

Aflatoxins

These molecules have been associated with lameness even though the mechanisms of action are not yet clear.

DON, Nivalenol, Fumonisins, Ochratoxins

These are all mycotoxins with effects on the integuments and consequently also on the feet.

HT-2 and T-2 Toxins

Well-known molecules for their vasoconstrictive action in mammals, they can therefore induce/provoke swelling or gangrene.

In general, MYCOTOXINS due to their antibiotic-like effects are responsible for the death of bacteria in the rumen and consequently the possible release of endotoxins (Baumgard et al., 2020) with general and local effects.

In cases of risk of mycotoxin presence in feedstuffs or in the ration or in the presence of manifest symptoms in the herd, it is necessary to supplement the diet with specific molecules capable of detoxifying mycotoxins, thus preventing their absorption and spread into the bloodstream.

Problems with Aflatoxins in Corn?

Mycotoxin contamination in food intended for human or animal consumption is a global problem, affecting both developed and developing countries. The presence of mycotoxins in food primarily causes issues with production efficiency, often associated with worsening health status, requiring more pharmacological interventions.

The widespread presence of aflatoxins in corn crops deserves attention as over 90% of the production is destined for livestock.

[…] Among the most used methods to reduce the negative effects of mycotoxin ingestion in pig farming is the use of adsorbents. Recently at ISAN, we evaluated the aflatoxin sequestration efficiency of different types of adsorbents by simulating the gastrointestinal environment of pigs. This research showed that various bentonites (Ca, Mg, and Na bentonite) and clinoptilolite are very efficient in sequestering these mycotoxins. Other products (zeolites, kaolinites, and yeast walls) widely used have been found to be less efficient. Therefore, the correct choice of the adsorbent to administer to animals appears critical to minimize the negative effects of mycotoxin ingestion, even at low doses. Nutritional measures aimed at increasing tolerance to some mycotoxins, such as the use of antioxidant molecules, should not be overlooked.